Socialising the losses and privatising the gains

The case of Cyprus five years after the bail-in of bank deposits

As pointed out in a recent IMF report,[1] “private sector indebtedness in Cyprus remains extremely high”. Politicians and banks, however, continue to present the non-performing loans (NPLs) as being the core problem of the economy. They argue that reducing NPLs is basically the same as providing a cure to the economy’s woes. However, NPLs is only a symptom of the real problem of the economy which, as pointed out by the IMF, is the enormous private debt. Focussing just on the need to reduce NPLs, while it may mitigate a bank’s need for additional capital, it is likely to make the bigger problem of private debt worse and harder to solve.

Indeed, the planned sale of bank loans to third parties, including to funds and asset management companies, while it will reduce the NPLs for banks and even enable some to show an accounting profit and ease their capitalisation needs, would leave borrowers with the same amount of debt that they presently owe. Moreover, the funds and companies that buy these loans at huge discounts from the banks would push for full repayment or collection of their dues through liquidating the collaterals and by claiming on the guarantees. Any margins that the banks may have through utilising the applied provisions for reducing or writing off a loan in a debt restructuring exercise will be squandered as discounts to the hedge funds and others to induce them to buy and thus take these NPLs off the bank’s balance sheets.

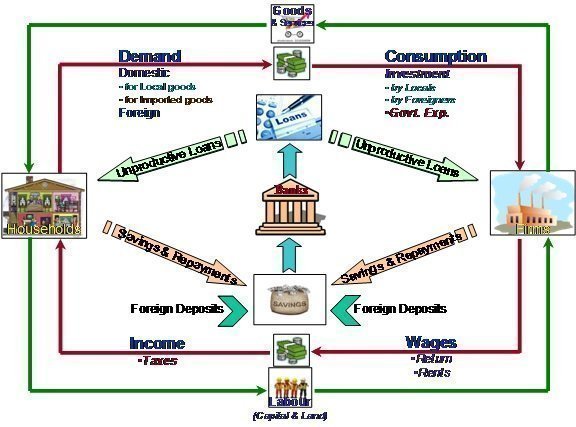

Private debt however still remains the key factor constraining households and firms from engaging in normal economic activity let alone allowing new investments. What is not widely understood is that it is imperative that finance is channelled towards economically viable capital investments in order to have sustainable economic development. If finance is used to fund unproductive investments in the economy the result will be a pile up of private debt which cannot be repaid and sooner or later will bring about a financial and economic crisis.

Another fallacy or misconception is the generally held belief that more finance is always better. What is not understood is that there is a need to keep a constant and balanced stream between the economic and financial flows. Too much finance available in the banking system will inevitably lead to financing unproductive investments. The need to position these extra deposits on income generating loans as quickly as possible will outweigh the requirement for applying prudent practices for identifying and funding economically viable projects. In any case, there are simply not enough such projects in a developed economy to justify the doubling or even trebling of deposits in the banks (usually from accepting overseas money). This is in fact what happened in Cyprus where over a period of 8 to 9 years foreign deposits in the banking system swelled to over six times GDP.

These deposits inevitably were lent out and were used for mostly unproductive purposes or to just finance consumption. The financial crisis of 2013 was an accident waiting to happen. It was a demon designed and nurtured for many years by those who had something to gain from such a loose control of the money flow from abroad, despite the clear indications that it would inevitably lead to a crisis. Private debt accumulated depleting the equity of economic agents and bringing the country to the brink of a crisis.

The imposed bail-in in 2013, apart from creating havoc, only treated the symptoms of the disease. The lessons that should have been learned were not. Instead, politicians found it convenient to argue that by saving the banks the economy would also be saved and be put back on the road of sustainable economic growth. But the country has been in denial for five years. The politicians in chorus in unison with mainstream academia keep reciting that if only the non-performing loans are somehow reduced or even eliminated from the balance sheets of the systemic banks the threat of another crisis will go away.

But the non-performing loans is only one symptom of the economy’s real problem which, as already mentioned, is the enormous private debt. This is likely to remain very high even if by some tool or method (such as the packaging and selling of loans) the current boards of the banks find a way to report a notional accounting profit and therefore avoid, at least temporarily, having to inject new capital into their ailing banks.

The abnormality of an economy which is being lumbered with the onus of having to pay a practically un-repayable mountain of private debt under conditions of weak economic growth cannot be overstated. In fact, Cyprus has avoided falling into a long and deep recession so far because borrowers were not actually servicing their loans (Manison and Savvides 2017). Instead, they kept channelling most of their available income and any remaining savings they had into consumption. This is in effect has sustained domestic demand to a level that has kept the economy going. Tourism has also helped in this respect as it has enhanced the demand for goods and services from foreigners who are not affected by the private debt locally.

Figure 1- Economic and Financial Flows

The impact of private debt and the inability of the economic agents to repay is illustrated in Figure 1. The economic and financial flows run concurrently but in opposite directions. However, it is not always apparent that these flows are inter-dependent. What happens in one flow affects the other. Collections on loans are repayments which in essence are savings flowing out of the economy and into the banks. But in situations of excessive private debt, such as the one enduring in Cyprus, where the economic conditions are not conducive for savings to be swiftly ploughed back into the economy in the form of productive loans, slowly but surely the economy drifts into another recession. The only way this can be mitigated is through fiscal policy measures and, in particular, Government spending in economically viable projects.

Richard Koo, based on similar experiences mostly from Japan, identified two conditions that are required to recover from an over-indebted economy. Clean balance sheets and viable investment opportunities. If these two conditions do not exist, or measures and policies are not undertaken to put them in place, then the most likely outcome is that the country will fall into a deep economic crisis which he calls a "balance sheet recession".

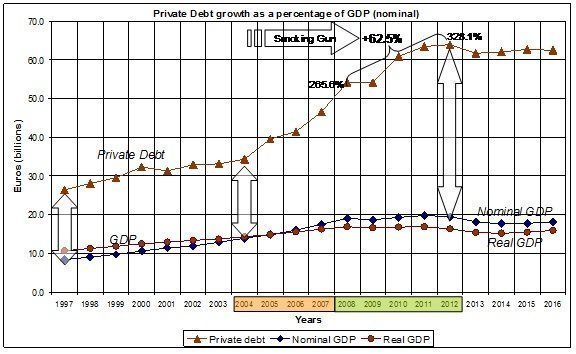

Sustainable development comes about only when funding is channelled to productive projects that generate incomes and adequate capacity for borrowers to repay loans and in addition provide a good return to the investor. In fact most economic crises result from a disconnect between funding and productive investments marked by an inability of the banking system as well as the economy to channel excess available finance into productivity. As illustrated in Figure 2, this is what happened in Cyprus leading up to the bail-in in 2013. Richard Vague among other prominent economists, that followed up on the classic exposition of the impact of private debt by Irving Fisher (1933) and Hyman Minsky (1986), such as Steve Keen (2011), identified a significant empirical regularity common to all economic crises: the combination of a private debt to GDP ratio of 150% or more, and a cumulative increase in that ratio over a five-year period of 17% or more (Vague, 2014). The data on Cyprus show that there was indeed such a smoking gun in place.

Figure 2- The disconnect of finance from productivity in Cyprus

Cyprus therefore created almost by itself an economic problem which could have been avoided, or at least contained, with a prudent financial policy. The myth conveniently created by some intermediaries who stood to gain from this is that Cyprus was becoming a miracle international financial centre. In fact it was nothing more than a smokescreen for them to profit despite causing huge collateral damage on the real economy.

The balance sheets of companies and households in Cyprus are now in the red (in negative equity or underwater) and in essence rendering the borrowers hostages at the mercy of the banks. And the banks, in turn, without an economic development perspective, only have the collaterals and guarantees of the loans to fall back on and try to recoup. This further reduces both the demand and the supply for new loans. So, an increase in savings in the form of repayments of existing loans will not find its way back into the economy in the form of productive loans. Because loans are hard to exist in conditions of feeble demand and where underwater balance sheets are more the rule rather than the exception.

But what makes the prospect of attaining sustainable development difficult is the fact that the over-indebted private sector cannot address the repayment of their loans without this impacting negatively on consumption. Good domestic demand is a prerequisite for having viable investment opportunities. Perhaps it is for this reason that the only important development that Cyprus has witnessed so far is in areas that do not depend directly on the existence of local demand, such as tourism and the sale of luxury properties to foreigners which, however, is dubiously driven by the lure of selling EU citizenship.

In conclusion, when an economy reaches such extreme scenarios where private debt is overwhelming, there are not many easy options available other than the reduction of debt. As Michael Hudson points out (Hudson, 2012) a debt that can’t be repaid will not be repaid. So any attempt to fix an over-indebted economy will have to include, in some form or another, significant debt forgiveness.

Such measures can in turn stimulate investment and also mitigate the effects of an inevitable decrease in consumption while loan repayments are in full flow. Moreover, a reduction of private debt must be further boosted with carefully planned public expenditure and investments in economically viable projects. This is the reason why it was argued (Savvides, 2016) that Cyprus needs to create a Development Agency or a Reconstruction and Development Bank that can competently and independently assess and lead the way for banks and other financial institutions to invest in viable projects (in both the public and private sectors).

Despite the many calls that have been made for creating such an organisation the Government has been slow to act, and now that things have come to the point where the capital adequacy of the banks is seriously threatened by the inevitable need to fully provide for NPLs, they are getting set to take the wrong option again by investing in the creation of a bad bank. It already seems that the Government, mainly through “supporting” the Co-op Bank, will purchase and take over the ailing bank’s NPLs at a suspected very high cost to the taxpayer. But what such an organisation is likely to become is no more than a dumping place funded by the taxpayer under which a high price is paid to take over bank obligations which are cast in stone against deteriorating assets. If the Government proceeds, as it seems to be its intention, to sell off the healthy part of the Co-op Bank that remains it will result in a situation of socializing the losses and privatizing the gains.

Moreover, a Government organisation that just gathers the NPLs of the banks will be confronted with two insurmountable problems. One is that without taking on a healthy loan portfolio it would not be able to have the income necessary to cover its operating costs, let alone for generating a return for the money invested by the taxpayer. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, without having in its portfolio loans that have a prospect of becoming viable there would be very little it can do to help the reconstruction and creation of new viable enterprises and ventures to be put back into the economy. This is indeed what the Cyprus economy gravely needs.

The need to repair and rebuild into new businesses the assets gathered in this manner is the main reason why the Reconstruction and Development Bank is proposed. Such a bank can do all that a “bad bank” can perform but also provide expert services and financing in economically viable projects where it is most needed. The focus of such an organisation is to cater for the need to create wealth rather than wealth extraction which currently seems to be the only aim. Moreover, as an independent professional organisation it will fill the need for providing competent advice and vetting of public sector and public-private partnerships (PPPs). Unfortunately, the latter need is played down by the Government because politicians always prefer to do such deals behind the scenes under the veil of a commissioned study which, more often than not, is put together to justify decisions already taken rather than aiding the decision making for the benefit of the economy as a whole.

Bibliography and References

- The second post-program monitoring mission, https://www.stockwatch.com.cy/en/article/oikonomia/imf-gdp-projected-grow-4-425-during-2018-2019

- Minsky Hyman P., 1986. “Stabilising an Unstable Economy”, McGraw-Hill Professional, New York.

- Vague Richard, 2014 “The Next Economic Crisis: Why It’s Coming and How to Avoid It”, University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Richard-Vague-on-Why-Large-Rapid-Build-Ups-of-Private-Debt-Cause-Financial-Crises

- Koo Richard C., 2015. "The Escape from Balance Sheet Recession and the QE Trap", Wiley.

- Hudson Michael, 2012. "The Bubble and Beyond. Fictitious Capital, Debt Deflation and Global Crisis", ISLET, Dresden.

- Keen Steve, 2011. "Debunking Economics: The Naked Emperor Dethroned?", Zed Books Ltd.

- Manison, Leslie Graeme and Savvides, Savvakis C., Towards Sustainable Growth (Rebuilding the Foundations of the Cyprus Economy) (May 23, 2016). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2784802 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2784802

- Fisher, Irving, 1933. “The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions”, Econometrica, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp.337-357.

- Manison, Leslie Graeme and Savvides, Savvakis C., Neglect Private Debt at the Economy's Peril World Economics Journal, Vol. 18, No. 1, January–March 2017,

- Treasury of the Republic of Cyprus, Financial Report 2015, http.www.treasury.gov.cy

- Savvides, Savvakis C., 2014. The Pursuit of Economic Development, Journal of Finance and Investment Analysis, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2014, Scienpress Ltd.

- Savvides, Savvakis C. Corporate Lending and the Assessment of Credit Risk, Journal of Money, Investment and Banking, Issue 20, March 2011.

- Savvides, Savvakis C., Overcoming Private Debt (Unblocking the Loan Burdened Real Economy in Cyprus) (June 20, 2016). The Journal of Private Equity, Fall 2016, Vol. 19, No. 4: pp. 51-59. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2784680

[1] The second post-program monitoring mission, https://www.stockwatch.com.cy/en/article/oikonomia/imf-gdp-projected-grow-4-425-during-2018-2019

3287.99

3287.99 1275.09

1275.09